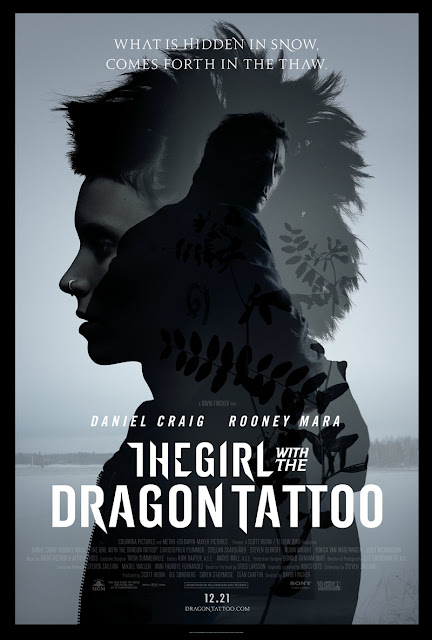

A literary phenomenon that has swept the globe,

Stieg Larsson's The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo arrives on the big screen courtesy of director

David Fincher and Academy Award-winning screenwriter

Steven Zaillian.

The result is a sturdily scripted, assuredly directed thriller that

gradually lures us into a labyrinthine mystery involving a discredited

journalist, a cryptic computer hacker, and a wealthy family harboring

some particularly dark secrets. Notably absent outside of the visually

striking (yet somewhat inexplicable) black-drenched credit sequence set

to

Trent Reznor and

Karen O's pulsing version of

Led Zeppelin's "Immigrant Song," however, is the dynamic and innovative visual style that has defined much of

Fincher's finest work.

Journalist Mikael Blomkvist (

Daniel Craig) has just lost a highly publicized court battle against powerful entrepreneur Wennerström (

Ulf Friberg) when he is summoned to the remote island estate of aging businessman Henrik Vanger (

Christopher Plummer),

who makes him a most-unusual proposition. Forty years ago, Henrik's

beloved great-niece Harriet vanished without a trace. Henrik is

convinced that someone in his family -- where greed and Nazism run

rampant -- has gotten away with murder, and despite the firestorm of

controversy over Blomkvist's credibility, he's certain that the seasoned

reporter can root out the killer. Meanwhile, as Blomkvist submerses

himself in a mystery decades in the making, misfit computer hacker

Lisbeth Salander (

Rooney Mara) finds her violent past returning with a vengeance thanks to her twisted new parole officer (

Yorick van Wageningen).

Before long, Blomkvist and Salander are working together as a team to

investigate the Vanger family, who all live on the same island yet

display an indifference to one another that often spills over into

outright animosity. But with each new clue that Blomkvist and Salander

uncover, the more apparent it becomes that Harriet's disappearance may

in fact lead them directly into an even darker mystery.

In

Seven and

Zodiac,

Fincher

used masterful pacing, atmospheric cinematography, and acute attention

to detail to seduce us into grim worlds of murder and obsession. Those

familiar themes are still very much propelling factors in

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, though this time

Fincher

comes off as much more restrained than usual. It's unclear whether

that's a result of his not being as emotionally invested in the material

or simply recognizing the need to get out of the way of a good story,

but by reteaming with cinematographer

Jeff Cronenweth (

Fight Club,

The Social Network),

Fincher still gives

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo

an exquisitely chilly visual scheme that provides a palpable sense of

atmosphere while holding the audience at arm's length. It's a good match

for a such a pulpy mystery, though a little of the director's trademark

inventiveness could have gone a long way in not only distinguishing

Fincher's take on the story from the previously filmed

Swedish-language version, but also in helping to connect the dots of

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo's somewhat contrived storyline.

An astonishing blend of dark allure and damaged brilliance,

Mara is compulsively watchable as Lisbeth Salander, while

Craig

effectively embodies quiet integrity as the humiliated reporter fleeing

the limelight while sharpening his investigatory skills. Compelling as

both characters are, however,

Fincher's

cool direction stunts any attempts to form an emotional connection with

them, even when Mikael and his daughter have a gentle conversation

about faith, or the scene in which Lisbeth bares her soul to her

investigative partner by confessing how she got caught up in the legal

system in the first place. And while a scene of shocking violence

between Lisbeth and her sadistic parole officer may be off-putting to

some, its contextual relevance is all but undeniable once we've learned

her darkest secret.

Given the lurid nature of

Stieg Larsson's story, it's easy to see why

Fincher

would be compelled to adapt it for the big screen. But it's impossible

not to feel like we've been down this road numerous times with the

director before. In

The Social Network, it felt as if

Fincher were truly growing as a filmmaker both thematically and stylistically. Despite being a solid mystery assuredly told,

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo

feels like something of a regression -- one that's largely absent of

the factors that established him as one of his generation's most

innovative filmmakers.